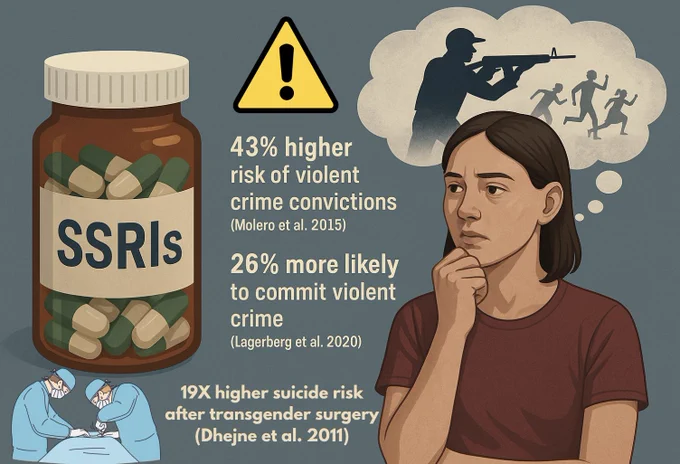

The balance of current evidence does not support the claim that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or other prescribed psychiatric medicines cause mass violence. Large population studies suggest, at most, a modest association between SSRI exposure and violent crime in adolescents and young adults, with no corresponding association in older adults, and the authors emphasise residual confounding and caution against causal inference. Replication in independent cohorts and under stricter designs has generally weakened initial signals, which is why the mainstream view remains sceptical of a causal link. Reviews focused specifically on mass shootings report no robust evidence that antidepressant treatment is a driver of such events.

Regulatory guidance is consistent with this cautious stance. Safety warnings highlight an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in people under 25 during early antidepressant treatment, which justifies close monitoring, yet these warnings concern suicidality rather than homicidal behaviour and do not imply a link to mass violence. Evidence syntheses using clinical study reports suggest increased risks of suicidality and aggression in children and adolescents on antidepressants, although methodological limitations and incomplete access to patient-level data limit the strength of the conclusions.

Context from adjacent pharmacoepidemiology points the other way for several classes of medicines. In Swedish within-person registry analyses, rates of violent crime were lower during periods when patients with severe mental illness received antipsychotics or mood stabilisers, and criminality among people with ADHD was lower during periods of stimulant treatment. These findings do not bear directly on SSRIs and mass shootings, but they illustrate that effective pharmacotherapy often reduces, rather than increases, risks linked to violence at the population level.

A prudent public health conclusion is therefore twofold. First, clinicians should monitor younger patients closely at treatment initiation and after dose changes, given the established suicidality signal in this age group. Second, claims that antidepressants contribute meaningfully to mass violence are not supported by high-quality evidence; research on mass violence points to heterogeneous motives and contextual factors, with no reliable medication effect identified to date. Continued use of rigorous methods such as pre-registration, data sharing and multi-site replications remains the most reliable route to resolving contested findings.