Co-founder of Future Ventures and DFJ, supporting passionate founders to forge a better future. Early VC investor in Tesla, SpaceX, Planet, Commonwealth Fusion.

Los Altos and San Francisco

Joined March 2010

- Tweets 10,387

- Following 69

- Followers 102,065

- Likes 15,915

🛰 Checking in on the XONA Pulsar, the first LEO GPS sat licensed by the FCC. They have just demonstrated the world’s best:

• precision: 10x better

• timing sync: 10x better (of keen interest to data centers)

• resilience: works 6x closer to jammers

• power consumption: 3x lower for receivers

• reach: it even works indoors

And all of these will improve as they add more sats — location to the cm and timing to the nanosecond.

Just as Planet improved earth observation and Starlink improved communications by flying many satellites closer to Earth, Xona is doing it for GPS.

Navigational intelligence: XonaSpace.com/

Go Xona, Go, Go, Go 🚀 🛰️

SpaceX successfully launched 70 satellites in one go, with the Xona Pulsar-0 bottom right. It is pioneering low-orbit GPS, of keen interest to the government as 150x power makes it harder to jam or spoof & much more precise:

xonaspace.com/news/launching…

How big is the Tesla Terafab?

Elon: “The only option is to build some very big chip fab. It’s at least 100K water starts per month. And that’s one of ten in a complex. So ultimately, it would be 1 million wafer starts per month.”

“We have to solve memory and packaging too.”

Tesla is going to build a gigantic chip fab.

Elon today: “We have to do a Tesla Terafab. It’s like Giga but way bigger. I can’t see any other way to get to the volume of chips that we are looking for. We are going to have to build a gigantic chip fab.”

“I am super hardcore about chips right now. I dream about chips. Literally.”

“Tesla is already the largest robot manufacturer in the world.”

Now with wheels, soon with legs. Affordable at $20K cost.

Oh, and another thing — Elon's new comp plan was approved, with over 75% voting in favor, to mad applause at the meeting. The shareholders have spoken.

Tesla is going to build a gigantic chip fab.

Elon today: “We have to do a Tesla Terafab. It’s like Giga but way bigger. I can’t see any other way to get to the volume of chips that we are looking for. We are going to have to build a gigantic chip fab.”

“I am super hardcore about chips right now. I dream about chips. Literally.”

“Tesla is already the largest robot manufacturer in the world.”

Now with wheels, soon with legs. Affordable at $20K cost.

Oh, and another thing — Elon's new comp plan was approved, with over 75% voting in favor, to mad applause at the meeting. The shareholders have spoken.

🤯 M͢i͢n͢d͢ ͢V͢i͢r͢u͢s͢e͢s͢

Catching the flu increases your risk of Parkinson’s disease by 90%

14 years later.

“The risk was specific for influenza, not any other infectious disease, and this increased risk showed up only a decade or more after the viral infection. Might getting vaccinated for seasonal influenza help stave off Parkinson’s? That’s an open question”

Quite simply, if we can avoid infection, will we avoid neurodegeneration? This is a huge downstream benefit of @Centivax’s universal flu vaccine program — one shot to end them all.

Shingles too: “Vaccination had a pronounced protective effect on the incidence of dementia. 1 in 5 new dementia diagnoses among unvaccinated people could have been averted by vaccination. If these are truly causal effects, then getting vaccinated for shingles is far more effective, far less risky and much less expensive than anything else out there now for dementia.”

— From the current issue of stanmed.stanford.edu/infecti…

P.S. pregnant women who get influenza in their second trimester give birth to children who are 7x more likely to have schizophrenia in adulthood.

🔥 @LatentAI is one of the 50 Hottest Edge Companies chosen by CRN and one of their top three edge specialists. Latent makes edge AI more efficient and compact — think drones, autonomous vehicles, robots, satellites, cameras and sensors of all kinds.

Moving AI from the cloud to the edge affords responsiveness, privacy, and real-time decision-making in contested, disconnected, and bandwidth-limited environments.

Steve Jurvetson retweeted

BREAKING: SpaceX has announced that @Starlink now has over 8 million customers, up from 7M in August and 6M in June 2025.

Starlink added a record 14,250 new customers on average per day since they hit 7M, beating their previous record of 12,200. That growth rate is 17% higher than it was just 2 months ago.

LF Go, Go, Go!!!

Best NASA pick ever. Thank you in advance for your service to this great nation!

Thank you, Mr. President @POTUS, for this opportunity. It will be an honor to serve my country under your leadership. I am also very grateful to @SecDuffy, who skillfully oversees @NASA alongside his many other responsibilities.

The support from the space-loving community has been overwhelming. I am not sure how I earned the trust of so many, but I will do everything I can to live up to those expectations.

To the innovators building the orbital economy, to the scientists pursuing breakthrough discoveries and to dreamers across the world eager for a return to the Moon and the grand journey beyond--these are the most exciting times since the dawn of the space age-- and I truly believe the future we have all been waiting for will soon become reality.

And to the best and brightest at NASA, and to all the commercial and international partners, we have an extraordinary responsibility--but the clock is running. The journey is never easy, but it is time to inspire the world once again to achieve the near-impossible--to undertake and accomplish big, bold endeavors in space...and when we do, we will make life better here at home and challenge the next generation to go even further.

NASA will never be a caretaker of history--but will forever make history.

Godspeed, President Donald J. Trump, and Godspeed NASA, as America leads the greatest adventure in human history 🇺🇸

🧠 Some good news on dementia: it's declined by 2/3 in the past 40 years.

From UCSF’s Future of the Brain Summit: physical activity reduces the risk of dementia by ~70%. It helps with blood vessel remodeling in the brain and higher synaptic signaling. Top advice: walk more.

🌋 Earth’s Mantle 🤯

It's 1,800 miles thick and makes up 84% of Earth’s volume. There is more water in our mantle than in our oceans.

We have never drilled deep enough to sample the mantle directly. But on an island in the aptly named Newfoundland, you can find Earth’s mantle transported to the surface.

I was given this fine sample at a recent Tesla event by someone who thought I might like it, and as I researched it, I found a newfound awe at how special the Earth’s inner dynamics are compared to other planets and moons.

First, the mantle is not solid rock, but a viscous fluid that circulates from the convection of heat from our molten core… circulating once per billion years! This circulation is the fundamental force driving plate tectonics and its side effects: earthquakes, volcanoes, and the formation of mountains.

Normally, the tectonic plates of Earth’s crust are subducted down deep into the mantle, recycling the surface of the planet. In the rare case of the Canadian Tablelands, the mantle was instead thrust up onto continental crust about 500 million years ago when continents collided.

This mantle sample is mostly the ultramafic rock peridotite, weathered here to a yellowish rusty color. Inside, the unaltered rock is a dark green olivine. It also embeds shiny flakes of mica.

The basalt that comes up from the mantle cools and slides over to the subduction zone over ~ 150 million years. Cool enough to start sinking, it is still lighter than the mantle, and for it to cycle back down, it has to become much more dense, and it does, 30 miles down, becoming eclogite which then sinks further into the mantle, which itself circulates as a viscous fluid down to our molten core, on a billion year roundtrip to circle back to the crust again. Without the materials marvel of eclogite, our plate-tectonic system would grind to a halt.

Only Earth has developed the habit of subduction, which has helped keep the planet on an even keel for eons. Subduction recirculates not only the solid ocean crust but also volatiles like water and carbon dioxide vented by volcanos back to the mantle. In contrast, other planets, like Mars with its fossil river valleys, have simply lost their volatiles to space over time, without a circulating reserve in its mantle.

Subduction circulates water down to the magma, forming granite (which accumulates in the continental crust), and lowering the viscosity of the mantle, allowing it to flow convectively, keeping the plates in motion. Granite is only found on Earth among the planets in our solar system.

Mars, lacks the movement of tectonic plates, enabling the largest volcanoes of our solar system to stay in one place erupting continuously for billions of years. In contrast, a volcano range, like the Hawaiian islands, leaves a chain of former cones sinking into the seabed all the way back to Japan.

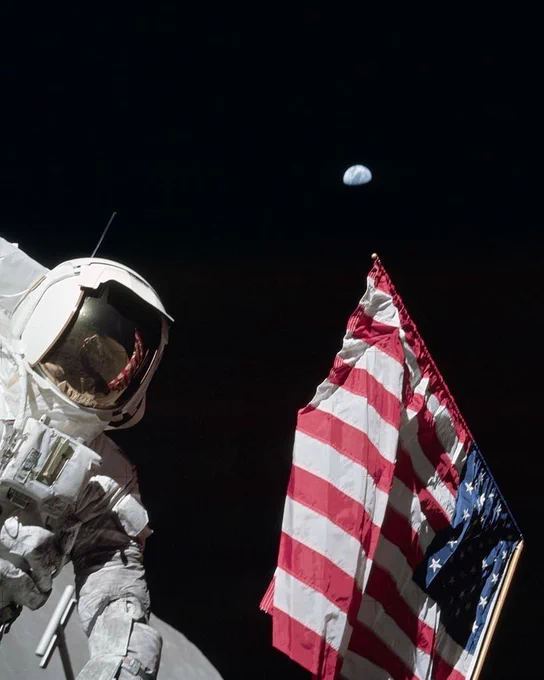

When SpaceX builds 𝕄𝕠𝕠𝕟 𝔹𝕒𝕤𝕖 𝔸𝕝𝕡𝕙𝕒, a permanent human settlement, we will finally have a generation who believes in the moon landing and the accomplishments of the human spirit. Imagine never having to hear from the conspiracy denialists again!

Imagine a permanently Earth-facing beacon that blinks in different patterns and colors to covey lunar activities (sleep, eat, exercise, rail gun practice…). Kids everywhere could see it with their own eyes with a simple binoculars.

And in the long arc of human history, we will skip from dream to dream... the closing passage from my Space Week keynote earlier this week:

Why do 1/4 of us think the moon landings were fake?

Worrisome on its own, it is part of a much larger phenomenon in false beliefs and mind viruses. Among young people in the U.S. and UK, the percent that think Apollo was faked has climbed steadily from 4% back when we were actually doing it to 25% today! (source: Ad Astra, 2019)

My prior post, showing the first Apollo 8 Earthrise, prompted hundreds of people to ask: “where are the stars?” and some to add the assertion that their absence proves the photo to be fake, one of the common arguments given for why the moon landing was faked. Such an odd chain of thinking.

The sheer number of such comments was shocking and disappointing to me. I feel like a Public Service Announcement is in order.

The starless black has an easy explanation, of course, for anyone who knows a bit about photography: no camera has the dynamic range to simultaneously capture a bright foreground object like the moon and the relatively dim background stars. You can overlay multiple digital photos, like an HDR merge, but none of that existed with the film cameras of the 60’s. Some people pointed out that you can verify this for yourself by taking a photo looking up to a streetlight at night. Or shoot a full moon in the night sky. If you can see any moon details, you won’t see any stars. The exposure setting can get one or the other but not both in a single shot.

Do you think any of the lunar lander deniers will go outside and try this simple experiment? I doubt any will (but maybe some just asked the question out of curiosity, and they will hopefully go get the answer for themselves). Please, do look up!

Will any evidence change a denier's mind? I used to hope so.

I once got into a long multi-day argument with someone who seemed to be making evidence-based claims that the rover rides were faked. I focused on why? Why go to all that effort? In the end, when backed into various logical corners, he stuck with the odd proposition that we wanted the Russians to know that our batteries were better than anyone’s, and thus, our terrestrial torpedoes had longer range. For some reason, we left it for them to deduce, like this wise conspiracy theorist had done, rather than just demonstrate it on Earth.

Getting into the mind of a denier is an exercise in frustration. 400,000 people worked on Apollo. To assert they all lied, and none gave an anonymous tip to the press, requires extraordinary evidence. Why land on the moon 6 times when once would suffice? Why not fake a Mars landing instead? Why would Russia, India and China separately go to the moon and verify that our landers are there? Why would our enemy in the space race agree that we did it? The mental contortions one witnesses if you actually try to have a conversation with a denier is decoupled from logic, reason or common sense. I used to think belief without evidence was reserved for religion. Imagine a world where everything is personal truth. Learning would cease. Back to the dark ages.

20 years ago, I wrote a blogger post on Spooks and Goblins asking:

“Do you think that the generation of myths and folkloric false beliefs has declined over time? In addition to the popularization of the scientific method, I wonder if photography lessened the promulgation of tall tales. Before photography, if someone told you a story about ghosts in the haunted house or the beast on the hill, you could choose to believe them or check for yourself. There was no way to say, ‘show me a picture of that Yeti or Loch Ness Monster, and then I’ll believe you.’ And, if so, will we regress as we have developed the ability to modify and fabricate photos and video?”

Well, here we are. Fabricating photos like the one for this post are easy. (As an aside, I tried 16 times to get Grok to render stars in the black sky on the moon, but it couldn’t overcome some embedded low-level knowledge about realistic exposures. Faking it is still hard. :)

In 2004, I co-taught a class with Larry Lessig at Stanford, and one of our texts by Posner shared the following statistics on American adults:

• 33% believe in ghosts and communication with the dead.

• 39% believe astrology is scientific (astrology, not astronomy).

• 49% don’t know that it takes a year for the earth to revolve around the sun.

• 67% don't know what a molecule is.

People’s willingness to believe untruths relates to the ability of the average person to reason critically about reality. Posner concludes: “It is possible that science is valued by most Americans as another form of magic.”

If “critical thinking” comes naturally from the scientific method, "magical thinking" flourishes in counterpoint. And those would be the dark ages. For most of human history, there was little to no progress. Almost no progress in a human lifetime. That was before the scientific method, a fundamentally better way for a culture to learn.

But the moon landing denial is a much more difficult topic than merely noticing rampant ignorance and the failings of our education systems.

Five years ago, the lunar rover argument on Facebook sparked some philosophical reflections that really got me thinking, and I'll share that here (it is public there too):

@PaulJeffries (a very smart person IMHO): “These views aren’t just ignorance (in the literal sense of not having knowledge), so they can’t be addressed by simply informing people of the truth.

The issues run much deeper. It’s a matter of epistemology, and a mindset where the priorities are about personal needs, more than knowledge which is inherently abstracted or depersonalized. The virtues of the scientific enlightenment, materialist mindset that is at issue are seen as unappealing by the people who reject “science”. They aren’t rubes who would believe science if only they heard the right claims; they’ve heard them. They fancy themselves as insightful resistors who seek a deeper truth.

If people feel disenfranchised, marginalized, hopeless, and feel that authority is suspect because it’s always been an instrument of oppression, they’re going to look for hidden truths (such as astrology) and ways to upset stagnation (such as political contrarianism). At the very least they’ll be disinterested in things that don’t seem to pertain to their own lives or questions or suffering or striving.

Similarly, they know that Trump “lies”; they think it’s epistemological jazz and his statements are code speak for a deeper truth. They are operational statements, not propositional ones. They won’t stop supporting Trump because you show them some “fact”, and they won’t stop trying to resist authoritarian oppression by ideology (as they see it) because you try to erase the sense that the world has meaning and purpose (as they seek it) by declaring scientific materialism and evolution.

Ironically (for those who are in the tech community and baffled by the statistics cited in the post), there’s a deep connection between American entrepreneurialism and resistance to received knowledge of science or historical fact or whatnot). We’re a frontier culture of pragmatists. We reject authority in our church history. We reject theory, just as we reject fancy theology. We rejected a distant king. We rejected book learning and notions of European social class pretenses (except as it suited our attempts at justification of chattel slavery).

It’s no accident that California in particular is the heart of innovation, where “weird” ideas that are very much not scientific materialism or received Judeo-Christian mainstream theology and metaphysics — weird spirituality —and weird art, weird communal living, weird hippy culture, on the physical frontier edge of a continent, all mix with the practical build it from nothing spirit of people who came looking for gold. No one can replicate Silicon Valley if they can’t capture the same admixture of irrationality, counterculture, anti-authoritarian experimentalism, pragmatism, commerce, autonomy, and sense that the world is to be synthesized at will, spun from whole cloth rather than an existing thing to be fought over and subdivided.

I’m not saying that ignorance is an essential currency of innovation. But those among us, and here I am speaking for example of myself, who embrace science and education and knowledge and also embrace skepticism about authority and entrepreneurship, should realize that the qualities we leverage and instantiate have similar roots to those we think are obstacles in a very different population. We are closer than it seems.

People who feel left behind, including by all the things we do in the tech frontier, will retreat to conservatism and skepticism and seek enlightenment in acts of revelation that feel authentic to them and are personally available and not reliant on distant authority.

If we want to find common ground or even one day common mission, it won’t just be a matter of a slight improvement in public schools or making sure everyone somehow “hears the word” of science.

Me: Fascinating. And worrisome, as this sounds like a self-amplifying bifurcation, creating a growing chasm of communication... to the point of mutual incoherence.

Pulled from proscriptive moorings, both sides can fall prey to modern prophets and revealed truth (one a contrarian superhero within, the other a belief in a protocol — an externalized process for accumulating progress).

Where is Karl Popper when we need him?

Paul Jeffries: “Yeah, I think you might be right. As I suggested, their ultimate roots are common. But there’s a self-feeding wedge of mutual incomprehension, contempt, and identity oriented around not being the other. As with politics in America too.

I should say I glossed over a complexity. There is a species of fanciful, humanistic, ambitious anti-science among the “costal elites” that is different than what you see among, for example, fundamentalist evangelicals. The former is folks who are denizens of tech (they might even be into crypto today; back in the day they were early BBS types, for instance) but into alternative medicine, vapor trails, vaccine skepticism, 9/11 conspiracies, remembered past lives, quantum mysticism, but also transhumanism and life extension and meditation and environmentalism and veganism and whatnot. They’re an admixture of perspectives and would grant the premise of common ground for debate and aren’t necessarily a part of a bifurcation wedge relative to adherents to received knowledge.

Those folks don’t think outside of mainstream received knowledge in the same way and for the same reasons as, say, creationist evangelicals. Although there are overlaps on things such as skepticism of the state and big business that play out as common ground on things like anti-vax.

The blue state / red state divide is self-amplifying.

The divides inside blue, which can include both mysticism and hyper pseudo-rationality, are perhaps more within a shared dialectic.

On another day it would be fun to explore whether one-way mass communications, and then the web, and then social media, amplified or diminished such differences, or just shed light on differences that were always there.”

S͙u͙p͙e͙r͙ ͙S͙p͙o͙o͙k͙y͙: I put my phone away and read this right before bed…🧟♂️

"Considered an 'urgent antimicrobial resistance threat' by the CDC, C. auris was first identified in a human patient in 2009, yet it could already fend off most antifungal drugs. The pathogen, which kills about one-third of the people it infects, unnerves physicians and public health officials not only with its invulnerability to treatment but to standard disinfectants: It easily colonizes skin and hospital equipment and then infects other patients and health care workers. C. auris turned up in the US in 2016 and rapidly spread across the country; it’s become so prevalent in some states that health care facilities can’t eradicate it.

Thanks to frequent misdiagnoses, no one knows exactly how many people die annually from fungal infections; estimates range as high as 3.8 million, more than AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria combined.

Climate change will surely spawn new virulent pathogens like C. auris. There’s a hypothesis that mammals thrived after the extinction of the dinosaurs in part because fungi couldn’t readily infect their warm-blooded bodies. Now, as all life on Earth tries to adapt to rising temperatures, endothermy may no longer save us. Even if The Last of Us isn’t quite our future, it’s not all science fiction, either."

— From: medicine.at.brown.edu/news/2…

I’m going to look for novel anti-fungal startups. For example, perhaps the novel mechanism of action in the RNA fungicide from Greenlight could help fight the proverbial zombie apocalypse: greenlightbiosciences.com/ar…

Today, from SpaceX: "Starship will bring the United States back to the Moon before any other nation, and it will enable sustainable lunar operations by being fully and rapidly reusable, cost-effective, and capable of high frequency lunar missions with more than 100 tons of cargo capacity... directly to the surface, including large payloads like unpressurized rovers, pressurized rovers, nuclear reactors, and lunar habitats."

— from: spacex.com/updates#moon-and-…

Starship really is that spacious... I've climbed through the mockup. Skylab comparison below. We can now establish a permanent human presence on the moon. Imagine seeing their lights from Earth each night... inspiring our spacefaring dreams.

Ad Lunae 🌖 That's Latin for LFG!