PhD student at Tsinghua NLP & AIR, studying agents that automate tasks ranging from daily activities to creative endeavors. Two drifters with the world to see.

Joined July 2017

- Tweets 1,263

- Following 2,154

- Followers 2,047

- Likes 9,036

Pinned Tweet

💪🦾Agentless Training as Skill Prior for SWE-Agents

We recently released the technical report for Kimi-Dev. Here is the story we’d love to share behind it: (1/7)

Zonghan Yang retweeted

New paper drop! 🎙️

We beat GPT-5 with a 36B model 🤯🤯

Not just better in terms of completing real-world complex tasks: software engineering (locating code) and deep research.

But also substantially better in terms of proactively asking for clarifying questions when necessary and interacting with users following their personalized preferences!

The secret comes from our PPP principle, which jointly optimizes the productivity, proactivity, and personalization of AI agents. Here, rewards come not only from the environment but also from simulated users. Just like in real life, we don’t learn solely from whether a task succeeds, but also from the feedback and reactions of our colleagues!

What’s even more exciting are the insights we gain from this work. For example, I often hear arguments that there’s no need to explicitly optimize for user interaction, and user satisfaction naturally follows from making the AI agent more productive (e.g., working for 40 hours non-stop). But not quite! You might see an initial boost in user satisfaction by focusing solely on task performance, but it can quickly decline once you push that optimization further (Figure 5 of the paper).

And there are many other experiments in the paper showing how the interaction between users and agents plays an important role in making things work better. Check out @sunweiwei12’s thread and the paper for more details!

AI agents are supposed to collaborate with us to solve real-world problems, but can they really? Even the most advanced models can still give us frustrating moments when working with them deeply.

We argue that real-world deployment requires more than productivity (e.g., task accuracy); agents must also be proactive in communication and personalized to individual user preferences.

Our new work introduces PPP, a Productive, Proactive, and Personalized optimization framework that explicitly trains LLM agents for effective human interaction.

🚀PPP achieves significant gains in complex, real-world agent–user scenarios (software engineering and deep research), outperforming even GPT-5 on both tasks with initially vague user instructions.

Zonghan Yang retweeted

Excited to release BFM-Zero, an unsupervised RL approach to learn humanoid Behavior Foundation Model.

Existing humanoid general whole-body controllers rely on explicit motion tracking rewards, on-policy PG methods like PPO, and distillation to one policy.

In contrast, BFM-Zero directly learns an effective shared latent representation that embeds motions, goals, and rewards into a common space, which enables a single policy zero-shot perform multiple tasks: (1) natural transition from any pose to any goal pose, (2) real-time motion following, (3) optimize any user-specified reward function at test time, etc.

How it works? We don't give the model any specific reward in training. It builds upon recent advances in Forward-Backward (FB) models, where a latent-conditioned policy, a deep "forward dynamics model" and a deep "inverse dynamics model"are jointly learned. In such a way, the learned representation space understands humanoid dynamics and unifies different tasks.

More details: lecar-lab.github.io/BFM-Zero…

Meet BFM-Zero: A Promptable Humanoid Behavioral Foundation Model w/ Unsupervised RL👉 lecar-lab.github.io/BFM-Zero…

🧩ONE latent space for ALL tasks

⚡Zero-shot goal reaching, tracking, and reward optimization (any reward at test time), from ONE policy

🤖Natural recovery & transition

Zonghan Yang retweeted

Discover DeepOCR: a fully open-source reproduction of DeepSeek-OCR, complete with training & evaluation code! #DeepLearning #OCR

We reproduce deepseek-ocr training from scratch, the code, model, results can be found in our website #DeepSeek

pkulium.github.io/DeepOCR_we…

Zonghan Yang retweeted

🚀 Hello, Kimi K2 Thinking!

The Open-Source Thinking Agent Model is here.

🔹 SOTA on HLE (44.9%) and BrowseComp (60.2%)

🔹 Executes up to 200 – 300 sequential tool calls without human interference

🔹 Excels in reasoning, agentic search, and coding

🔹 256K context window

Built as a thinking agent, K2 Thinking marks our latest efforts in test-time scaling — scaling both thinking tokens and tool-calling turns.

K2 Thinking is now live on kimi.com in chat mode, with full agentic mode coming soon. It is also accessible via API.

🔌 API is live: platform.moonshot.ai

🔗 Tech blog: moonshotai.github.io/Kimi-K2…

🔗 Weights & code: huggingface.co/moonshotai

Zonghan Yang retweeted

Hey @agarwl_ , thanks for your attention! For most small-scale experiments we used 8xA100 & the sanity check setting; for larger dense or MoE training we used 64xH100 & the 'normal' setting (DAPO dataset).

We also did not observe severe collapse until we develop the "sanity check" setting - a small dataset with all solvable questions (we can expect 100% rewards in theory and we empirically got 98%). We think this is a clean setting to test any algorithm before we scale it up to massive dataset and GPUs.

Using large dataset (plus algorithmic fixes like TIS or CISPO) can slow down the collapse or make it never happen in practice, despite the mismatch exists

Zonghan Yang retweeted

🚀Excited to share our new work!

💊Problem: The BF16 precision causes a large training-inference mismatch, leading to unstable RL training.

💡Solution: Just switch to FP16.

🎯That's it.

📰Paper: arxiv.org/pdf/2510.26788

⭐️Code: github.com/sail-sg/Precision…

Zonghan Yang retweeted

You see:

- a new arch that is better and faster than full attention verified with Kimi-style solidness.

I see:

- Starting with inferior performance even on short contexts. Nothing works and nobody knows why.

- Tweaking every possible hyper-parameter to grasp what is wrong.

- Trying to find the efficient chunkwise parallelizable form to squeeze juice out of the GPU

- RoPE or NoPE, a question haunting for nights.

- Fighting buggy implementation that causes one of the long-context benchmarks drops ~20 pts.

- RL diverging. Aligning training-inference numerics.

- Dedicated efforts to make sure comparisons are solid and fair.

- Going back-and-forth in a pool of adversarial gate-keeping tests, and finally it survives.

Great teamwork!

Kimi Linear Tech Report is dropped! 🚀

huggingface.co/moonshotai/Ki…

Kimi Linear: A novel architecture that outperforms full attention with faster speeds and better performance—ready to serve as a drop-in replacement for full attention, featuring our open-sourced KDA kernels! Kimi Linear offers up to a 75% reduction in KV cache usage and up to 6x decoding throughput at a 1M context length.

Key highlights:

🔹 Kimi Delta Attention: A hardware-efficient linear attention mechanism that refines the gated delta rule.

🔹 Kimi Linear Architecture: The first hybrid linear architecture to surpass pure full attention quality across the board.

🔹 Empirical Validation: Scaled, fair comparisons + open-sourced KDA kernels, vLLM integration, and checkpoints.

The future of agentic-oriented attention is here! 💡

Zonghan Yang retweeted

Can AI automate jobs?

We created the Remote Labor Index to test AI’s ability to automate hundreds of long, real-world, economically valuable projects from remote work platforms.

While AIs are smart, they are not yet that useful:

the current automation rate is less than 3%.

Zonghan Yang retweeted

I am excited to share a work we did in the Discovery team at @GoogleDeepMind using RL and generative models to discover creative chess puzzles 🔊♟️♟️ #neurips2025

🎨While strong chess players intuitively recognize the beauty of a position, articulating the precise elements that constitute creativity remains elusive. To address this, we pre-trained generative models on public datasets and then applied reinforcement learning, using novel rewards designed for uniqueness, counter-intuitiveness, realism, and novelty. This approach doubled the number of novel chess puzzles compared to the original training data, while successfully maintaining aesthetic diversity.

Three distinguished experts—International Master of chess compositions Amatzia Avni (author of "Creative Chess"), Grandmaster Jonathan Levitt @JonathanLevitt7 (author of "Secrets of Spectacular Chess"), and Grandmaster Matthew Sadler @gmmds (author of "Game Changer")—evaluated and selected the puzzles they found most compelling. Their preference was for puzzles exhibiting original, paradoxical, surprising, and naturally occurring positions, with particular emphasis on those that integrated aesthetic themes in innovative ways and demonstrated exceptional over-the-board vision.

🧩Try to solve the puzzles @chesscom: chess.com/c/2wCTN7Uv2

Zonghan Yang retweeted

The passing of the physicist Chen-Ning Yang (nytimes.com/2025/10/18/scien…) saddens me. He has been a long-time hero and role model for me. Below is a short essay I wrote yesterday about Yang that I shared with many of my friends. I translated it into English using Gemini:

```

The passing of Professor Chen-Ning Yang has left me with an inexplicable sense of loss, a feeling that a familiar era is slowly coming to an end. When Kolmogorov passed away in 1987, Kiyosi Itô wrote in his eulogy, "When I learned that the great Soviet mathematician Kolmogorov had left this world, I felt a sadness and loneliness as if I had lost a pillar of support." My relationship with Professor Yang was certainly not as direct as Itô's with Kolmogorov, but his influence, transmitted through his books, articles, and recorded lectures, profoundly changed the course of my life.

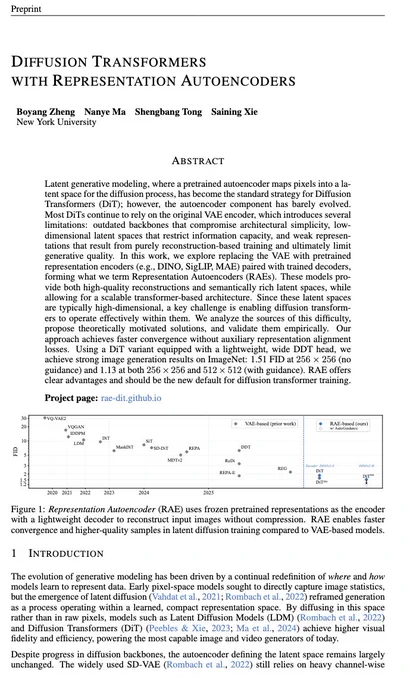

When I first came to the U.S., I would often introduce myself in the physics department by saying, "Yang from Yang-Mills." Later, when I was struggling to choose between physics and mathematics, I came across an interview with Yang and Jim Simons where he said two things that stuck with me (Figure 1): "Mathematics is precise, but there is no flesh to it," and "There are two kinds of books in math. The first one you read the first page and you stop reading. The second one that you read the first sentence and stop reading." Those words resonated with me so deeply that I decisively gave up on mathematics. This choice filled my university life with many more interesting physics pictures, making it much more vivid.

Later, as I contemplated my future path, I read online about Yang's famous advice against going into particle physics ("the party is over"). He remarked, "When I compare people who entered graduate school in the same year, I find that they all started in more or less the same state, but their developments ten years later were vastly different. This wasn't because some were smarter or more diligent than others, but because some had entered fields with growth potential, while others had entered fields that were already in decline, or even at their very end." This deeply struck me. Indeed, gauge theory is a more vital direction than particle physics because it naturally builds connections with many different disciplines. Inspired by this, I began to seriously ask myself: what is the "gauge theory" of our time? That's what led me to start researching neural networks in my junior year.

As I gained more experience in research, I found numerous inspirations in Yang's annotated collection, "Sixty Years of My Career Path." Right now, this book is on my bedside table. What resonated with me most was his note on his paper about the two-dimensional Ising Model (Figure 2): "In the spring of 1951, Oppenheimer showed me a preprint he had just received. For this, I carried out a very long calculation, the longest of my life. The calculation was tortuous, full of obstacles at every turn, requiring many strategies and tricks to solve. Often, after days of intense thought, I would suddenly discover a new technique, a new path would appear. The trouble was that I would soon feel lost in a maze again, unable to be sure if I was any closer to the goal than when I started." Yang's description here was so relatable that later, whenever my research stalled, I would share this quote with my collaborators to encourage everyone. I often found myself translating this passage into English for them.

As I spent more time living in the United States, I inevitably encountered some prejudice and discrimination against Chinese people. This reminded me of a story I had read about Yang from 1954. By then, he had already secured a tenured position at Princeton and was only three years away from winning the Nobel Prize. Yet, a real estate agent refused to sell him a house simply because he was Chinese, fearing that his presence would lower property values in the area. Even a man of Yang's stature could not escape such baseless and absurd prejudice. Later, while working at Google's New York office, I made a memorable trip to Long Island to visit the area where he used to live. This brought to mind his speech at the Nobel banquet in 1957: "I am in more than one sense a product of both the Chinese and Western cultures, in harmony and in conflict. I should like to say that I am as proud of my Chinese heritage and background as I am devoted to modern science, a part of human civilization of Western origin."

And now, life has come full circle. This semester, I've begun studying the derivation of the mass gap in three-dimensional Euclidean Yang-Mills theory (Figure 3) to fulfill my last graduation requirement. A familiar and friendly intuition returns. Although Professor Yang has passed away, his work, his ideas, and his intuition have been distilled across the entire internet. I randomly sampled 10B tokens from the DCLM dataset and found 1392 documents containing variations of his name in English and Chinese (Figure 4). His thoughts have genuinely become a part of humanity's collective knowledge. Finally, in his outlook on physics, Yang cautioned against the optimism that "the power of human intellect is infinite, while the depth of natural phenomena is finite". In this unique era of artificial intelligence development, this sixty-year-old debate seems particularly interesting.

```

Introducing RL-100: Performant Robotic Manipulation with Real-World Reinforcement Learning. lei-kun.github.io/RL-100/

7 real robot tasks, 900/900 successes. Up to 250 consecutive trials in one task, running 2 hours nonstop without failure.

High success rate against physical disturbances, zero-shot, and few-shot adaptation

Our first step toward a deployable robot learning system.

Zonghan Yang retweeted

Sneak peak from a paper about scaling RL compute for LLMs: probably the most compute-expensive paper I've worked on, but hoping that others can run experiments cheaply for the science of scaling RL.

Coincidentally, this is similar motivation to what we had for the NeurIPS best paper on reliable evaluation: I did 100s of RL runs, so others can just get by with a handful of runs.

Zonghan Yang retweeted

three years ago, DiT replaced the legacy unet with a transformer-based denoising backbone. we knew the bulky VAEs would be the next to go -- we just waited until we could do it right.

today, we introduce Representation Autoencoders (RAE).

>> Retire VAEs. Use RAEs. 👇(1/n)

Thank you @gm8xx8 for being the die-hard fan!🤘🏻

Thank you Rohan @rohanpaul_ai for the highlight!

The Kimi-Dev paper shows Coding agents work better when they first learn a fixed workflow that builds core skills.

Gives a low-friction recipe to build strong coding agents without huge agent datasets. the training uses verifiable steps, costs less, and is easier to debug.

The workflow model scores 60.4% on SWE-bench Verified, and the agent version gets 48.6% pass@1 after 5K trajectories.

Pass@1 means single try success on each problem.

Multi-turn agents are flexible but hard to train because feedback is late and runs are long.

So the authors use agentless training as a skill prior, covering file finding, code edits, and self-checks.

They split the job into 2 roles, a BugFixer that writes patches and a TestWriter that builds failing and then passing tests.

They pretrain on real GitHub diffs and commits, start the model with long reasoning traces, and apply reinforcement learning only to edits.

At test time the model plays both roles, makes many patches and tests, then picks the patch that passes tests.

A small supervised finetune on 5K agent trajectories adds stronger multi-turn behavior with longer, more useful reflections.

The core blueprint is to teach stable, checkable skills first, then transfer them to a flexible agent with little extra data and compute.

----

Paper – arxiv. org/abs/2509.23045

Paper Title: "Kimi-Dev: Agentless Training as Skill Prior for SWE-Agents"

To me this is a moonshot project at @Kimi_Moonshot . Fortunate to collaborate with a group of talented members of technical staff: @ShengjieWa34067, @instropg13, @YingweiM98560, and many others! Grateful to be able to work through the days and nights, and growing with a thriving community of coding agents. 💪🦾

More experiments and case studies are in the report (arxiv.org/abs/2509.23045).

This work reflects our research exploration. Improved with a meticulously refined recipe, our flagship model Kimi-K2-0905 delivers much enhanced agentic coding capability and user experience. (7/7)

Performance:

5k trajs over the Agentless RL model = 48.6% with a single attempt under SWE-Agent setup.

5k SWE-Agent trajs over the Base ≈ 100 trajs over the Agentless RL model.

The fewer the trajs, the better the perf is for the model with stronger Agentless skill priors. (6/7)

Starting from the Base model, these skills are gradually strengthened through Agentless mid-training, cold-start, and RL.

We finetuned the ckpts in each stage with public SWE-Agent trajectories from SWE-Smith (huge shoutout to @jyangballin @KLieret et al.!), and inspect how the skill priors transfer: (5/7)