Padre, GameDev(Unreal Engine) y Software Developer, en ese orden. Siempre yendo para adelante por vos. - las opiniones son mias -

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Joined January 2010

- Tweets 69,895

- Following 225

- Followers 403

- Likes 182,330

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

Caputo habló ante inversores en el JP Morgan.

La pregunta es, por qué le da información a inversores del sistema financiero y no a todos argentinos?

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

🐀Son ratas coludas.

Después de crecer a base de los vendedores que a riesgo propio abrieron nichos de productos.

MercadoLibre, en una suerte de manejo de información privilegiada, tomó esa información y trajo los productos por su cuenta.

Perjudico a sus propios socios, o mejor dicho, los utilizo y los tiro como un forro usado.

Ahí no se preocuparon por los puestos laborales.

The hunt begins. Join the Predator: Badlands experience in select Fortnite Creative Islands. Climb from Unblooded to Warlord, build your Trophy Wall, and unlock exclusive Predator cosmetics:

Pandvil Box Fights (2v2): 6562-8953-6567 | (3v3): 7686-1102-4551 | The Pit: 4590-4493-7113

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

BREAKING: According to a reliable source, this is the stage of development GTA 6 is in.

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

Fine-tune DeepSeek-OCR on your own language!

(100% local)

DeepSeek-OCR is a 3B-parameter vision model that achieves 97% precision while using 10× fewer vision tokens than text-based LLMs.

It handles tables, papers, and handwriting without killing your GPU or budget.

Why it matters:

Most vision models treat documents as massive sequences of tokens, making long-context processing expensive and slow.

DeepSeek-OCR uses context optical compression to convert 2D layouts into vision tokens, enabling efficient processing of complex documents.

The best part?

You can easily fine-tune it for your specific use case on a single GPU.

I used Unsloth to run this experiment on Persian text and saw an 88.26% improvement in character error rate.

↳ Base model: 149% character error rate (CER)

↳ Fine-tuned model: 60% CER (57% more accurate)

↳ Training time: 60 steps on a single GPU

Persian was just the test case. You can swap in your own dataset for any language, document type, or specific domain you're working with.

I've shared the complete guide in the next tweet - all the code, notebooks, and environment setup ready to run with a single click.

Everything is 100% open-source!

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

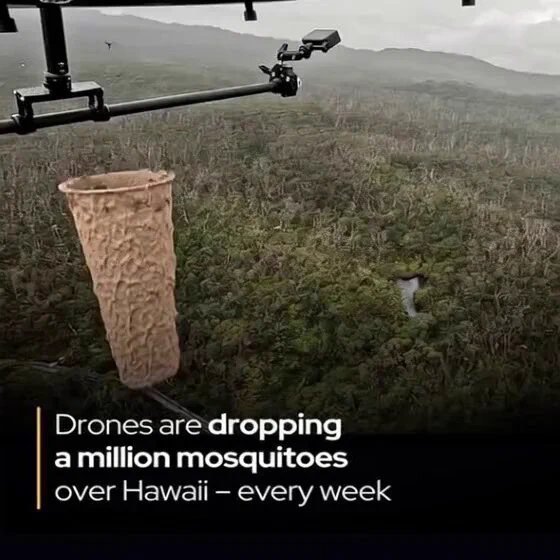

A million mosquitoes are falling from the skies over Hawaii every week.

To rescue some of Hawaii’s rarest birds from extinction, scientists are releasing one million mosquitoes into the wild—every week.

These are not ordinary mosquitoes. They are lab-bred males that don’t bite and are sterilized by a natural bacterium. When they mate with wild females, the eggs fail to hatch. Flood the forest with enough of these incompatible males, and the mosquito population crashes.

That collapse could save Hawaii’s honeycreepers—vibrant, jewel-like birds that once filled the islands with song. More than 50 species existed; only 17 survive, and most are on the brink.

The primary killer isn’t habitat loss. It’s avian malaria, carried by invasive mosquitoes that arrived in the 1800s. Native birds have no immunity. For decades, they survived only in cool, high-elevation refuges where mosquitoes couldn’t thrive. But warming temperatures are pushing the insects upward, and the birds have nowhere left to go.

Enter the Incompatible Insect Technique (IIT). The released males carry a strain of Wolbachia bacteria that renders cross-mating sterile. Packed into biodegradable pods, they’re deployed by drone and helicopter across steep, inaccessible terrain.

Currently, 500,000 mosquitoes are released weekly on Maui and another 500,000 on Kauai.

This is the largest use of IIT ever attempted to protect wildlife, not people.

If it works, it could give critically endangered birds like the ʻakekeʻe and kiwikiu a fighting chance to rebound—and perhaps even develop resistance. But conservationists warn: the window is closing fast.

["Thousands of mosquitoes are being dropped by drone over islands in Hawaii. Here’s why." Science, 5 November 2025]

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

This movie was worth it.

.

.

.

This movie was beyond what I thought.

.

.

.

The heart, The Action, The Visuals, The art work put on screen.

.

.

.

This movie was amazing.

#yautja

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

WE DID IT

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

I understand if anyone doesn't like the design but it needs to be taken into consideration that it's literally the entire point of the movie that Dek is an underdog runt who doesn't look like other Yautja and is ostracized for it. Other Yautja in the film have the classic look.

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

Wait till these bozos find out that Female Yautjas are Bigger and STRONGER than Male Yautjas....they're gonna cry WOKE despite them being around for 30 years. #PredatorBadlands

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

🔥En agosto les anticipé el desplome del 30% en paquetería de MercadoLibre

- Lejos quedaron los días donde Galperin ventilaba números de ventas para sostener la idea de crecimiento de consumo, siendo usado por el propio Milei como argumento.

- En cantidad de entregas: tanto Día de la Madre como Cyber Monday no despegaron siendo históricamente sus grandes eventos. Dejando logística ociosa debido a la falta de paquetes.

- No solo lo azota la recesión, tiene otros frentes abiertos: Quedaron caros, se encuentra mejor precio en la calla de "contado".

- El éxito de Shein y Temu termino de ponerlos de los pelos. Cosa que se plasmó en el llanto de su presidente pidiendo regular el mercado.

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

Es una psyop increíble, te llevan al límite extremo de ver hasta donde llegas sin reivindicar el nazismo.

La DAIA, a través de su Secretaría de Lucha contra el Antisemitismo en el Deporte y su Centro de Estudios Sociales, se reunió ayer con autoridades del club San Fernando para evaluar la acción de un socio adulto de dicha entidad, que vistió una remera con la inscripción "SAVE GAZA" en el tercer tiempo luego de un partido de jockey entre ese club y Macabi.

El encuentro fue altamente positivo ya que las autoridades de San Fernando dejaron en claro que no avalan ninguna clase de antisemitismo ni discriminación y que su Comisión Direcitva se encuentra estudiando las medidas a tomar con el socio.

Se acordó producir una agenda de trabajo entre San Fernando y la DAIA consistente en brindar capacitaciones a los profesionales deportivos y jugadores, además de generar visitas al Museo del Holocausto.

Se continuará con esta línea de trabajo a fin evitar el antisemitismo en el deporte.

ShadowDrone ⭐️⭐️⭐️ retweeted

BREAKING: Turkey has issued arrest warrants for Benjamin Netanyahu and 36 Israeli officials, accusing them of genocide and crimes against humanity committed in Gaza.

Queeww buena que estuvo Predator Badlands locoo. QUE Universo se viene. Que ojo q tiene Kojima con la pibita Fanning

Increibleee